Understanding the Glycemic Index: A Practical Guide for Blood Sugar Management

The glycemic index has become a cornerstone concept in diabetes management and blood sugar control. This numerical ranking system provides valuable insight into how different carbohydrate-containing foods affect blood glucose levels. Understanding and applying glycemic index principles can significantly improve glycemic control and reduce the risk of blood sugar spikes that contribute to long-term complications.

What is the Glycemic Index?

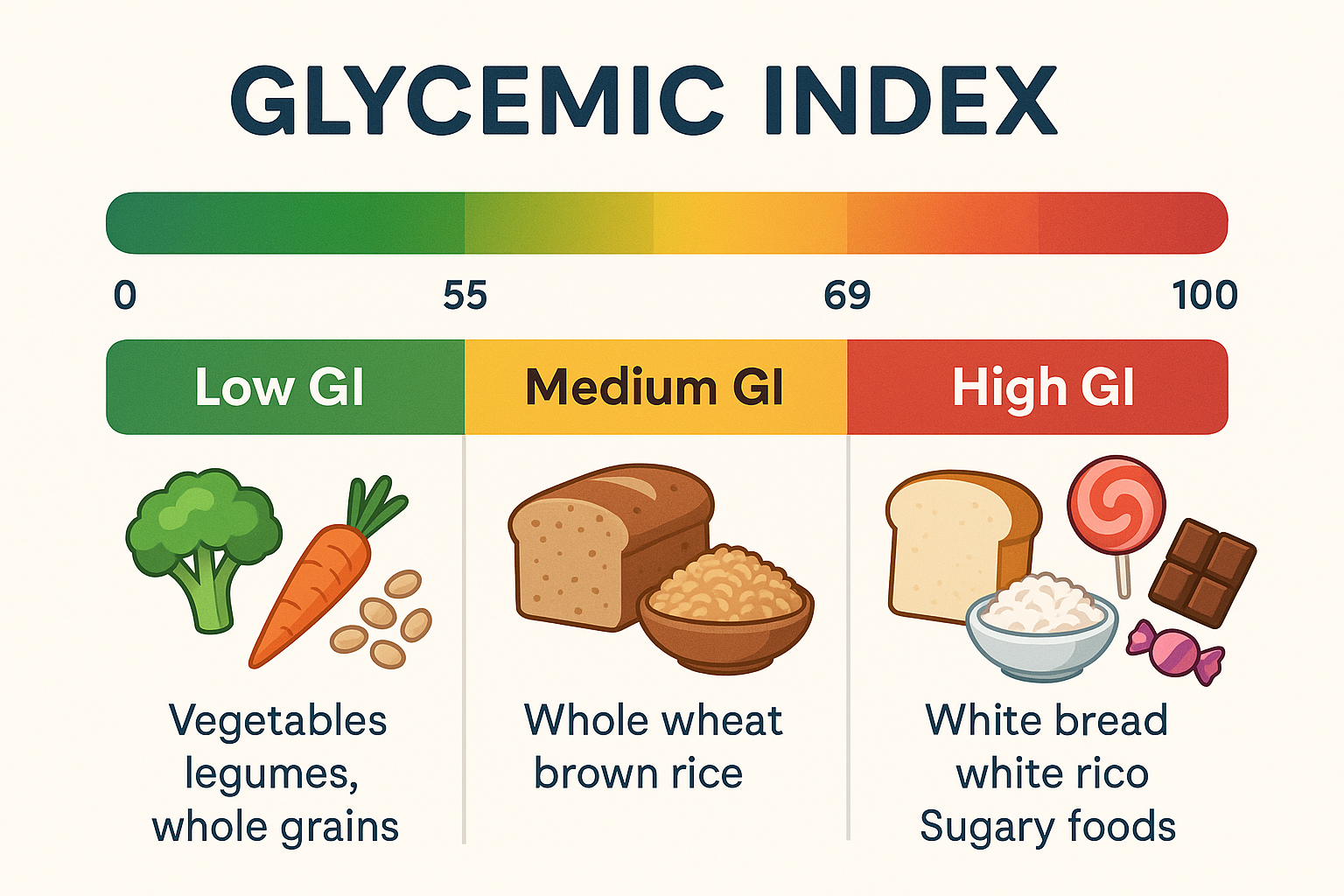

The glycemic index (GI) is a numerical scale from 0 to 100 that measures how quickly a carbohydrate-containing food raises blood glucose levels compared to pure glucose or white bread. Foods are tested in controlled laboratory settings where healthy volunteers consume a portion containing 50 grams of available carbohydrate, and their blood glucose response is measured over two hours.

The resulting blood glucose curve is compared to the response from consuming 50 grams of pure glucose (or sometimes white bread), which serves as the reference standard with a GI of 100. A food’s GI value represents the percentage of the glucose response it produces. For example, a food with a GI of 70 raises blood glucose to 70 percent of the level that pure glucose would produce.

This standardized testing methodology allows for consistent comparisons across different foods, though individual responses can vary based on factors such as insulin sensitivity, meal composition, food preparation methods, and personal metabolism.

The Three GI Categories

Foods are classified into three categories based on their glycemic index values, each with distinct implications for blood sugar management.

Low GI Foods (55 or below) are digested and absorbed slowly, producing gradual rises in blood glucose and insulin levels. These foods provide sustained energy without dramatic spikes. Examples include most non-starchy vegetables, legumes, whole grains like steel-cut oats and barley, most fruits, nuts, and dairy products. Low GI foods are generally recommended as dietary staples for individuals with diabetes or insulin resistance.

Medium GI Foods (56-69) produce moderate blood glucose responses that fall between low and high GI foods. This category includes foods like whole wheat products, brown rice, sweet potatoes, and some tropical fruits like pineapple and mango. These foods can be incorporated into a balanced diet but should be consumed in appropriate portions and ideally combined with protein or healthy fats to moderate their glycemic impact.

High GI Foods (70 and above) are rapidly digested and absorbed, causing sharp spikes in blood glucose and insulin levels. This category includes white bread, white rice, most breakfast cereals, potatoes, sugary snacks, and refined grain products. While not forbidden, these foods should be limited and, when consumed, paired with low GI foods, protein, or fat to reduce their overall glycemic impact.

Why the Glycemic Index Matters for Diabetes

For individuals with diabetes or pre-diabetes, the glycemic index provides a practical framework for making food choices that support stable blood glucose levels. Consistently choosing lower GI foods helps prevent the dramatic blood sugar fluctuations that strain the body’s glucose regulation system and contribute to long-term complications.

High GI foods trigger rapid glucose spikes that demand large insulin responses. For people with type 2 diabetes who already have insulin resistance, this creates additional metabolic stress. The pancreas must produce even more insulin to handle these glucose surges, accelerating beta cell exhaustion. Over time, this pattern worsens glycemic control and may necessitate increased medication.

Low GI diets have been shown in numerous studies to improve HbA1c levels, reduce fasting blood glucose, and decrease insulin requirements. These diets also help with weight management, as low GI foods tend to be more satiating and reduce hunger between meals. The gradual glucose release prevents the energy crashes and subsequent cravings that often follow high GI meals.

Beyond immediate glucose control, low GI eating patterns reduce inflammation, improve lipid profiles, and may lower cardiovascular disease risk. These benefits extend beyond diabetes management to overall metabolic health.

Factors That Influence Glycemic Index

The glycemic index of a food is not fixed but can be influenced by numerous factors related to food composition, processing, and preparation methods.

Fiber content significantly lowers glycemic index. Soluble fiber forms a gel-like substance in the digestive tract that slows carbohydrate absorption. This is why whole grains have lower GI values than their refined counterparts. For example, steel-cut oats (GI 55) have a much lower glycemic index than instant oatmeal (GI 79) due to their higher fiber content and less processed structure.

Fat and protein both slow gastric emptying and carbohydrate digestion, reducing the glycemic response. Adding nuts, cheese, or olive oil to a meal lowers its overall glycemic impact. This is why full-fat dairy products often have lower GI values than low-fat versions, and why combining carbohydrates with protein sources improves blood sugar control.

Food processing and cooking methods dramatically affect GI values. Processing that breaks down food structure increases glycemic index. Mashed potatoes have a higher GI than whole boiled potatoes. Fruit juice has a higher GI than whole fruit because the fiber has been removed. Longer cooking times generally increase GI by breaking down resistant starches.

Ripeness affects the GI of fruits and vegetables. As produce ripens, starches convert to sugars, raising the glycemic index. A green banana has a lower GI than a fully ripe banana. This is why choosing slightly underripe fruit can be beneficial for blood sugar control.

Acidity lowers glycemic response. Adding vinegar or lemon juice to meals can reduce their glycemic impact. This is one reason why sourdough bread has a lower GI than regular bread—the fermentation process creates organic acids that slow digestion.

Practical Application: Using GI in Daily Life

While understanding glycemic index theory is valuable, the real benefit comes from practical application in everyday eating. Here are strategies for incorporating GI principles into your daily routine.

Start with breakfast. Choose low GI options like steel-cut oats with nuts and berries, Greek yogurt with seeds and fruit, or eggs with vegetables and whole grain toast. Avoid high GI breakfast cereals, white toast, and pastries that set up blood sugar instability for the entire day.

Build meals around low GI carbohydrates. Replace white rice with brown rice, quinoa, or cauliflower rice. Choose sweet potatoes over white potatoes, or if eating regular potatoes, cool them after cooking to increase resistant starch content. Select whole grain or legume-based pasta instead of refined wheat pasta.

Never eat high GI foods alone. If you choose to eat a higher GI food, always combine it with protein, healthy fats, or low GI foods. Add nuts to dried fruit, pair bread with avocado and eggs, or include a large salad with your pasta dish. This “food pairing” strategy significantly reduces the overall glycemic impact of the meal.

Emphasize non-starchy vegetables. Most vegetables have very low GI values and can be eaten freely. Fill half your plate with vegetables at each meal to dilute the glycemic load and provide fiber, vitamins, and minerals that support metabolic health.

Choose whole fruits over juice. Whole fruits contain fiber that moderates their glycemic impact, while fruit juice produces rapid blood sugar spikes. When eating fruit, pair it with a protein or fat source—apple slices with almond butter, berries with Greek yogurt, or an orange with a handful of nuts.

Glycemic Index vs. Glycemic Load

While glycemic index is valuable, it has limitations that led to the development of a related concept called glycemic load (GL). Understanding both metrics provides a more complete picture of how foods affect blood sugar.

Glycemic index measures the quality of carbohydrates—how quickly they raise blood glucose—but doesn’t account for quantity. A food can have a high GI but contain very little carbohydrate per serving, resulting in minimal actual blood sugar impact. Conversely, a low GI food eaten in large quantities can still cause significant glucose elevation.

Glycemic load addresses this limitation by multiplying a food’s GI by the grams of carbohydrate in a typical serving, then dividing by 100. This calculation produces a number that reflects both the quality and quantity of carbohydrates consumed.

For example, watermelon has a high GI of 76, which might suggest avoiding it. However, a typical serving contains only about 11 grams of carbohydrate, resulting in a low glycemic load of 8. This means watermelon, despite its high GI, has minimal impact on blood sugar when eaten in reasonable portions.

Conversely, brown rice has a medium GI of 68, but a large serving containing 45 grams of carbohydrate produces a glycemic load of 31, which is quite high. This illustrates why portion control remains important even when choosing lower GI foods.

Glycemic load categories are defined as: low (10 or less), medium (11-19), and high (20 or above). For optimal blood sugar control, aim for individual meals with a glycemic load under 20 and a total daily glycemic load under 100.

Common Misconceptions About Glycemic Index

Several misconceptions about the glycemic index can lead to confusion or inappropriate dietary choices.

Misconception: All low GI foods are healthy. While many low GI foods are nutritious, the glycemic index doesn’t measure overall nutritional value. Ice cream has a relatively low GI due to its fat content, but it’s not a health food. Conversely, some nutritious foods like watermelon and potatoes have higher GI values but provide valuable nutrients and can be part of a healthy diet when consumed appropriately.

Misconception: High GI foods must be completely avoided. The goal is not to eliminate all high GI foods but to be strategic about when and how you consume them. High GI foods eaten in small portions, combined with low GI foods, or consumed after exercise when muscles are primed to absorb glucose can be managed effectively.

Misconception: GI values are the same for everyone. Individual glycemic responses vary based on insulin sensitivity, gut microbiome composition, stress levels, sleep quality, and other factors. Some people experience larger blood sugar spikes from certain foods than others. Continuous glucose monitoring can help identify your personal responses.

Misconception: Glycemic index is the only factor that matters. While GI is valuable, overall diet quality, total carbohydrate intake, meal timing, portion sizes, and lifestyle factors like exercise and sleep are equally important for blood sugar management. GI should be one tool among many, not the sole focus of dietary planning.

Combining GI Knowledge with Other Dietary Strategies

The glycemic index works best when integrated with other evidence-based dietary approaches for diabetes management.

Carbohydrate counting and GI principles complement each other. Knowing both the quantity and quality of carbohydrates you consume provides comprehensive blood sugar control. You might choose to consume 30 grams of carbohydrate at a meal, but selecting low GI sources will produce better glycemic outcomes than high GI choices.

The plate method can be enhanced with GI awareness. The standard recommendation to fill half your plate with non-starchy vegetables (all low GI), one quarter with protein, and one quarter with carbohydrates becomes even more effective when that carbohydrate quarter consists of low GI options like legumes, quinoa, or sweet potato.

Intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating can be combined with low GI eating. When you do eat, choosing low GI foods helps maintain stable blood sugar during fasting periods and prevents the rebound hunger that can derail fasting protocols.

Low-carbohydrate and ketogenic diets naturally emphasize low GI foods by restricting carbohydrates overall. However, even within these frameworks, choosing lower GI carbohydrate sources when you do consume them optimizes blood sugar control.

Practical GI Food Swaps

Making simple food substitutions can dramatically lower the glycemic impact of your diet without requiring complete dietary overhaul.

Breakfast swaps: Replace corn flakes (GI 81) with steel-cut oats (GI 55), or white toast (GI 75) with whole grain sourdough (GI 54). Choose Greek yogurt (GI 11) instead of sweetened flavored yogurt (GI 33).

Lunch and dinner swaps: Substitute white rice (GI 73) with brown rice (GI 68), quinoa (GI 53), or cauliflower rice (GI 15). Replace white pasta (GI 49) with whole wheat pasta (GI 37) or legume-based pasta (GI 28-35). Choose sweet potatoes (GI 63) over white potatoes (GI 78), or try mashed cauliflower as a potato alternative.

Snack swaps: Replace crackers (GI 71) with raw vegetables and hummus (GI 6), or rice cakes (GI 82) with apple slices and almond butter (GI 38). Choose dark chocolate (GI 23) over milk chocolate (GI 43), or fresh fruit (GI 25-55) instead of dried fruit (GI 60-70).

Bread swaps: Select whole grain sourdough (GI 54), pumpernickel (GI 50), or sprouted grain bread (GI 43) instead of white bread (GI 75). Even better, replace bread with lettuce wraps, collard green wraps, or coconut flour tortillas for very low GI alternatives.

Monitoring Your Personal Response

While published GI values provide useful guidelines, individual responses vary. Personal monitoring helps identify which foods work best for your unique metabolism.

Blood glucose monitoring remains the gold standard for understanding your glycemic responses. Testing before and two hours after meals reveals how specific foods affect your blood sugar. Over time, this data helps you identify patterns and make informed choices.

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) provide even more detailed information, showing the complete glucose curve after meals and revealing delayed or prolonged glucose elevations that fingerstick testing might miss. CGMs can identify surprising individual responses, such as blood sugar spikes from foods generally considered low GI.

Symptom tracking complements glucose monitoring. Note energy levels, hunger, cravings, and mood after different meals. Low GI meals should provide sustained energy without crashes, reduced hunger between meals, and stable mood. If you experience different results, adjust your food choices accordingly.

HbA1c trends over months reflect the cumulative impact of your dietary choices. If you’ve shifted toward lower GI eating, you should see gradual HbA1c improvements over 3-6 months, assuming other factors remain constant.

Conclusion: GI as a Tool for Empowerment

The glycemic index is not a rigid rule system but rather a flexible tool that empowers informed food choices. By understanding how different carbohydrates affect blood sugar, you can make strategic decisions that support stable glucose levels, reduce medication requirements, and improve overall metabolic health.

The goal is not perfection but progress. Small shifts toward lower GI choices accumulate into significant improvements in glycemic control. Start with one meal per day, gradually expanding your low GI repertoire as you discover foods you enjoy. Combine GI awareness with other diabetes management strategies for comprehensive blood sugar control.

Remember that context matters. The same food can have different effects depending on portion size, meal composition, timing, and your current metabolic state. Use GI values as general guidelines while paying attention to your personal responses through monitoring and symptom awareness.

With consistent application, glycemic index principles become second nature, transforming from conscious effort into intuitive eating patterns that support long-term health and well-being.